1 | Secular Morality

Growing up, I learned that goodness meant obeying God's commands. But years later, I began to notice a problem: some of those commands, taken at face value and acted upon, didn’t sit right — they clashed with my gut instinct about what was fair, compassionate, or humane. Could God be wrong? Was God evil? Why would he even suggest such things?

That tension led me to ask a different question: are we reading the Bible the wrong way? Rather than simply obeying it, perhaps we ought to analyse it. Perhaps good and evil lie in the common-sense nature of the action itself — and perhaps the Bible, in its own way, affirms this.

This essay begins with a common-sense understanding of morality before cross-examining whether the Bible reaches those same conclusions — and what happens when it doesn’t.

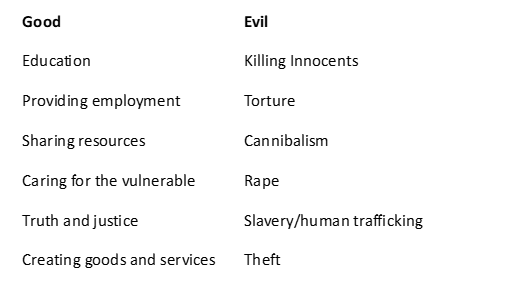

A Table of Good and Evil Deeds

What Patterns Emerge?

Looking at these examples, certain patterns become clear:

Evil acts typically:

Involve harm that the perpetrator would never want inflicted upon themselves

Serve the self at the direct expense of others

Deny or ignore the humanity and consciousness of others

In summary, evil appears to involve treating other humans as objects rather than conscious beings with their own agency, dreams, and right to life.

Good, by contrast, seems to hinge on respect for life—encompassing human consciousness, agency, and dignity. Good acts typically:

Treat others as we would wish to be treated

Promote and act in service to human flourishing

Recognize that human flourishing is interconnected

Universal Human Recognition

Everyone knows that we ought to protect the vulnerable—it's an instinct that doesn't come from textbooks, but from our shared human experience and a natural capacity for empathy: seeing ourselves in others.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights captures this common-sense understanding perfectly:

"All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood."¹

Philosopher Ayn Rand echoed this principle when she argued that "the moral justification of capitalism is man's right to exist for his own sake, neither sacrificing himself to others nor sacrificing others to himself."²

Whether expressed through human rights declarations or economic philosophy, the core insight remains: where human dignity is diminished, we instinctively recognize evil; where it's honoured and protected, we naturally see good.

When Common Sense Gets Disrupted

Yet, the question must be asked—if the distinction between right and wrong is so obvious, why do good people sometimes do terrible things? Even our most basic moral instincts can be corrupted—often by forces that disguise themselves as virtue. These forces distort empathy, making harmful acts seem necessary, righteous, or even good. History and contemporary case studies show this pattern again and again.

1. The ancient Maya sacrificed young boys to their rain god Chaac, throwing them into sacred cenotes believing this would ensure rainfall and fertile fields.³ Ignorance drives such acts—when people don't understand natural causes, they seek supernatural explanations and solutions.

2. In contemporary Africa, thousands of children are accused of witchcraft. In just two Nigerian states, 15,000 have been abused, abandoned, or killed—often because neighbours, relatives, or religious leaders reinforce the accusation.⁴ Cultural pressure overwhelms individual conscience—social conformity can override moral instincts.

3. Today, 12 million girls marry before age 18, with families often selling daughters for survival.⁶ In Niger, 76% of girls marry before 18, not because parents don't love them, but because they see no other path to security.⁷ Desperation makes exploitation seem like the only option.

4. Historical genocides and religious wars often begin with dehumanising the "other" to rally unity within the tribe or faith. Tribal identity enables such horrors—loyalty to a group, religion, or nation can lead people to excuse harm against outsiders, rationalising cruelty as "defence" or "justice."

5. In war zones, civilians sometimes betray neighbours or participate in violence under threat of punishment or death. Fear and survival instinct may justify acts they'd otherwise condemn.

In each case, moral judgement and instinct are surrendered to external authorities—cultural norms, economic pressures, or survival instincts, showing that what ought to be common sense can actually be very complicated.

2 | Biblical Morality

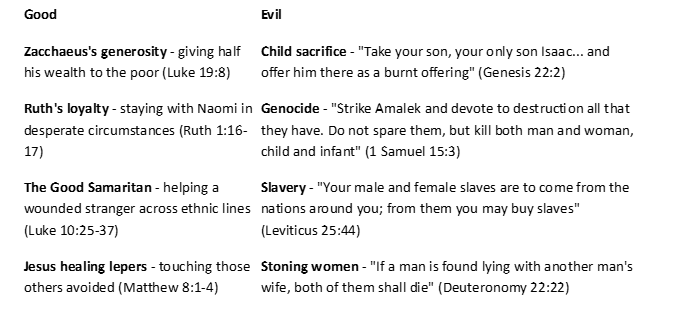

When we apply our common-sense morality to biblical stories, we are met with the conflict of evil deeds being commanded by what is supposed to be a "good God."

The Problem of Religious Bias

Many people today have been conditioned to believe "if it's in the Bible, it's good" or "if God commands it, it's righteous"—even when their gut tells them otherwise. This represents a dangerous surrender of moral reasoning to external authority.

But what if there's another way to read and interpret these passages?

A Secular-Biblical Interpretation: Think, Don’t Obey

If we set aside the assumption that every biblical command is divinely endorsed, a pattern emerges: the Bible often shows good people doing evil things and reveals that following orders—even from the highest authority—does not guarantee righteousness. This reflects reality.

The Bible's genius may lie not in providing a list of rules to follow, but in forcing us to think for ourselves and exercise detachment from authority: Could some biblical commands that seem morally troubling be included not to approve of them, but to test and sharpen the reader's own moral judgment?

The story of Abraham suggests this possibility: "And it came to pass after these things, that God did tempt Abraham" (Genesis 22:1, KJV). The word "tempt" suggests a test of moral judgment, not an unquestionable directive.

In daily life, we must take on the responsibility of judging whether a command is good or evil—not through the lazy route of considering who provides the command, but by exercising empathy and putting ourselves in another person's shoes. Or, to use one of Jesus's own philosophies as a guiding principle: "Love your neighbour as you love yourself" (Matthew 22:39).

Conclusion: What is Good and Evil?

When our instinct for empathy and fairness conflicts with an authority's command—and we choose obedience over conscience—the results can be devastating. History is filled with examples: atrocities committed in the name of religion, cultures entrenched in injustice, and individuals who cause harm while believing they are doing good. On a personal level, the habit of outsourcing moral judgment erodes our capacity to think critically, numbs our empathy, and makes us dependent on others to tell us right from wrong. In both cases, the cost is the same: moral responsibility is abandoned, and human dignity is the casualty.

This topic is the beginning of an expansive exploration. In this essay, we examined defining good and evil and encountered the challenge of bias. We've seen that good and evil are defined in relation to other people. Good respects life, dignity, and agency; evil denies them. Bias arises when we measure morality primarily by its benefit to ourselves—or when we conflate obedience with righteousness.

The central question remains: Should we prioritize who gives a command or what the command actually asks us to do? The evidence suggests we must judge the action itself, using our capacity for empathy and our instinctive understanding of human dignity. When we surrender this moral responsibility to any authority—religious, cultural, or political—we risk becoming complicit in evil, regardless of how good our intentions might be.

This exploration raises further questions:

To what degree is our instinct for right and wrong corrupted by associating morality with obedience?

To what degree is blind obedience the root of systemic evil?

How should institutions structure themselves to resist corruption and maintain moral clarity?

The answers to these questions may determine whether humanity continues to progress toward greater dignity and flourishing, or whether we repeat the tragic patterns of history where good people do terrible things simply because someone in authority told them to.

References:

Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Article 1. United Nations, 1948.

Rand, Ayn. Capitalism: The Unknown Ideal. New American Library, 1966.

Barquera, R., et al. "Ancient DNA from Chichén Itzá reveals genetic ancestry of sacrificed children." Nature, June 2024.

"Witchcraft accusations against children in Africa." Al Jazeera, November 2018.

"Child sacrifice in Uganda." World Hope International, 2023.

"Child marriage facts." UNICEF DATA, October 2019.

"Countries with the highest child marriage rate as of 2022." Statista, May 2023.